SNFC

Sierra Nevada Fire Chronosequence

The mixed conifer forests of the Sierra Nevada, like many forests of the Western United States, are evolutionarily adapted to frequent, low-severity fire. Prior to European settlement, these forests would experience light, surface fires that would maintain ecosystem health by mineralizing nutrients for plant uptake and clearing small trees to allow for an open park-like canopy. However, with the onset of fire suppression (and absence of same surface fires), plant densities have increased. Now, when fires do burn, they burn at a higher severity than the biota are adapted to.

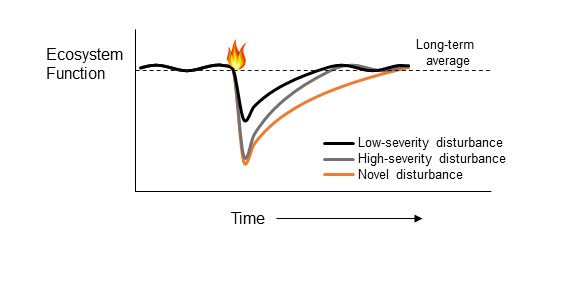

We know that these high-severity fires have resulted in large changes in the aboveground ecosystem (lots of dead trees and stunted recovery), but we know relatively little about the impacts belowground, which could impact the recovery of the overall ecosystem. We hypothesize that the resillience to this novel disturbance (i.e., disturbance with severity outside the historical range of variation) is much lower than other ecosystems.

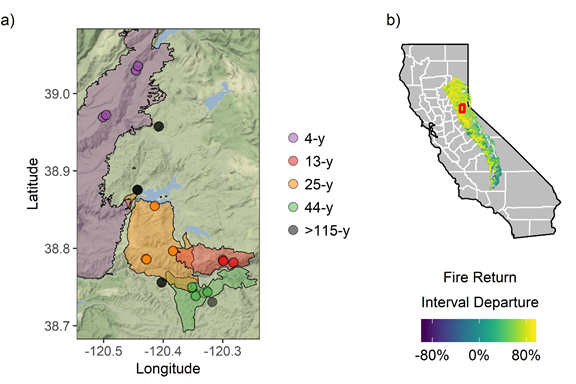

To test this hypothesis and elucidate the mechanisms of soil recovery, we set up a fire chronosequence in the Central Sierra Nevada, a highly fire-suppressed region. A fire chronosequence is a method of simulating long-term recovery of fire. We use time-for-spcae substitution, which basically means we go to locations (spaces) that burned at different times in the past. By controlling for different soil types, climates, vegetation, etc., we can assume that the recovery trajectory of these different locations is similar. Hence, we can track the recovery of the ecosystem through time.

We are using a traditional biogeochemical assays coupled with next-generation sequencing of microbial DNA to look at the recovery of the microbial communities and their function in response to high-severity fire.

The first paper in this project was just recently published in Ecological Applications. Check back soon for updates on more publications associated with this work.